A new study has found that people who have a tendency to believe in pseudoscience also have a tendency to jump to conclusions. In two games, participants were asked to solve a puzzle and given evidence or clues to help them in the process. They were free to stop collecting evidence and make up their minds at any point during these experiments.

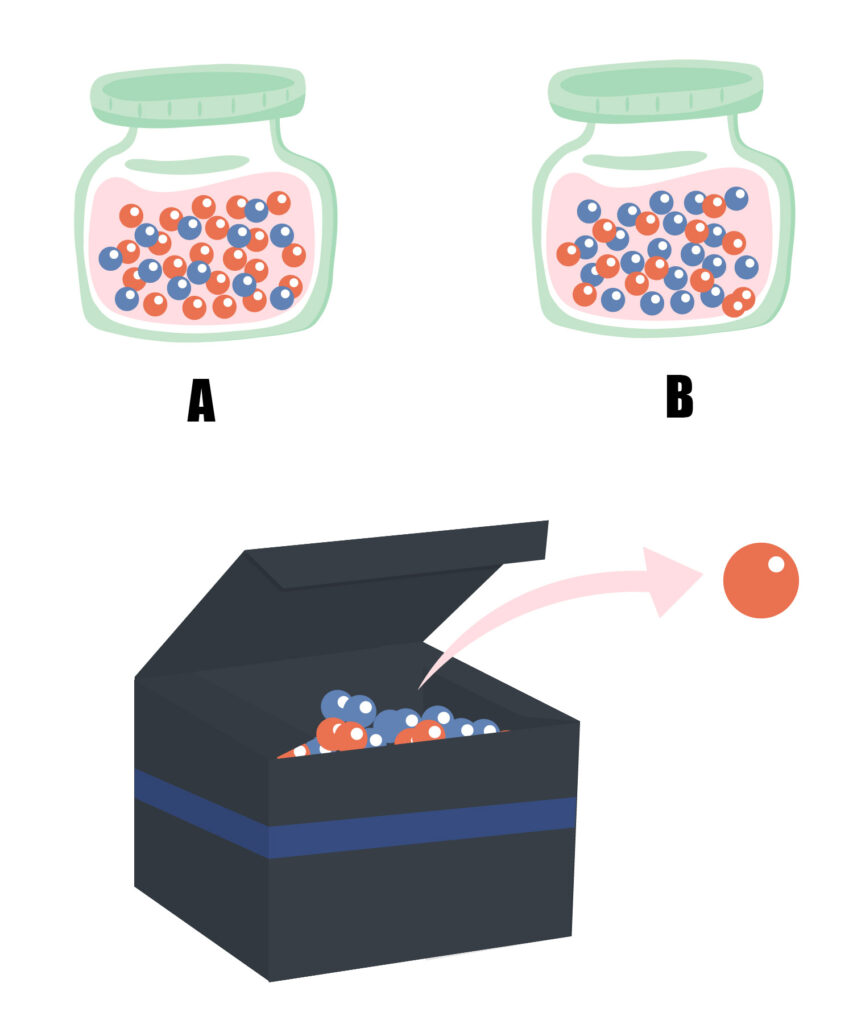

In the first experiment, participants were shown two jars. One contained 60 red beads and 40 blue beads (mostly red jar) and the other contained 60 blue beads and 40 red beads (mostly blue jar). They were then given a box into which the contents of one of the jars had been poured. Their task was to determine if the beads came from the mostly red jar or the mostly blue jar.

Researchers took out the beads from the box one by one and showed it to the participants to help them decide. The same color sequence of beads were presented to every participant. The first one taken out of the box was always blue, the second was always red, and so on. At any point during this process, participants could ask the researchers to stop if they had made up their minds.

After this experiment was over, participants answered a questionnaire (Pseudoscience Endorsement Scale) designed to measure their belief in pseudoscience. They were asked how much they agreed with statements like “Listening to classical music, such as Mozart, makes children more intelligent.”; “It is possible to control others’ behaviour by means of subliminal messages” and “A positive and optimistic attitude towards life helps to prevent cancer”.

The study found that the more pseudoscientific beliefs a person had, the sooner they stopped drawing beads from the box and made up their minds. People who had a tendency to believe in pseudoscience were quick to choose a jar; in other words, jump to a conclusion.

In another game, participants saw a ‘mouse’ and a piece of cheese within cells in a 3X3 grid on a computer. Participants could move the ‘mouse’ in any direction using keys on a keyboard. However, there was a secret rule that decided whether the mouse got the cheese or not – if the mouse reached the cheese after 4 seconds since the start of the game it got the cheese, and if it got there within 4 seconds or less, it did not get the cheese.

The participant’s task was to figure out this secret rule by playing the game. They could play the game a maximum of 100 times. When they felt they had discovered the rule, as in the previous game, they could stop playing and report their answer to the researchers.

Once again, the number of times a participant played the game correlated negatively with their score on the Pseudoscience Endorsement Scale.

“Our results indicate that, compared to sceptics, individuals presenting stronger endorsement of pseudoscientific beliefs tend to require less evidence before coming to a conclusion in hypothesis testing situations.”

The study suggests that people who tend to believe in pseudoscience are hasty when testing a hypothesis, easily satisfied with evidence and quick to jump to conclusions. Read more about the study by Javier Rodríguez‑Ferreiro and Itxaso Barberia here.